So far, we've seen that blockchain technology could be applicable to use cases beyond money and store of value thanks to smart contract platforms like Ethereum, Hyperledger, EOS, NEO, Cardano, DFINITY, and others which allow code to be stored and executed on-chain as a backend for decentralized applications. Each platform has its unique features and tradeoffs that determine its suitability for different use cases. While I won't be comparing these platforms in detail here, in this article we will explore the scalability trilemma - the three perspectives from which we can evaluate different blockchain and protocol implementations.

Creating and securing stores of value traditionally involved digging for gold, turning it into gold bars, and then storing them underground again for safekeeping. Cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, as stores of value, exist as math and code, secured through energy-intensive protocols like proof-of-work. For the masses to adopt a global, financially inclusive digital store-of-value, the network it runs on needs to be decentralized and secure. However when considering complex use cases beyond store of value, we also need to be able to transact at scale (speed).

As we will see in a bit, it may not be feasible for monolayer blockchains to score high on all three properties. Therefore, second-layer (L2) solutions like Plasma, Raiden, Lightning, TrueBit and RSK are exploring structures that anchor to a main blockchain as a root of trust, with scalability features implemented in higher layer(s). The largest, oldest, and most reliable PoW blockchain right now is of course Bitcoin. While many L2 solutions are building on a newer blockchain, what can we do to improve the scalability and programmability of bitcoin itself?

Before we go further here are some of my previous articles that serve as primers for the things we'll be discussing : Introduction to Bitcoin | Smart Contracts & Ethereum | Cryptography & Transactions | Proof of Work & Mining | Proof of Stake & Cryptoeconomics

In this post I will be exploring how we may leverage the decentralization and security of the Bitcoin network to run decentralized applications at scale, and dive into the Rootstock project which is tackling this very problem. First, some introductory concepts...

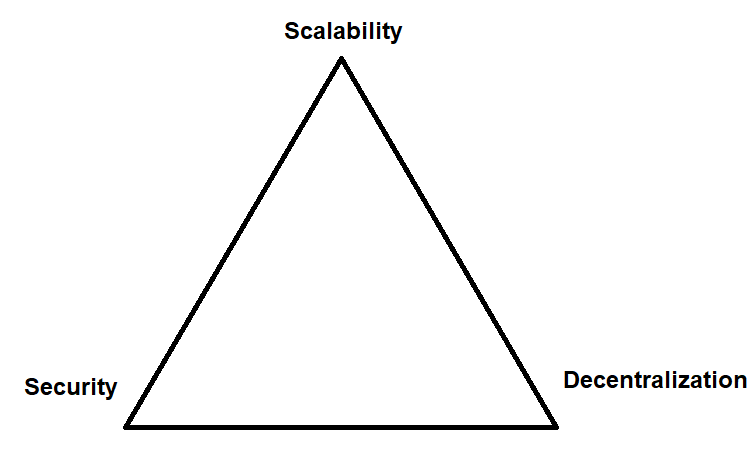

The Scalability Trilemma

The trilemma claims that blockchain systems can only at most have two of the following three properties:

Decentralization enables censorship-resistant, permissionless networks that allow anyone to partake in an ecosystem

Security pertains to the immutability of the ledger and its general resistance to attacks such as 51% attacks, Sybil attacks, DDoS attacks etc.

Scalability refers to the ability to process transactions on any given network. If blockchains can be mass-adopted, they have to be able to handle a scenario in which there are millions of users on the network.

This means that the layer 1 blockchains we know today that scores highly in more than one of the three aspects lie in the shaded area of one of these triangles:

For example, today Bitcoin and Ethereum are strong on the decentralization and security aspect at the expense of scalability, which without layer 2 technologies, puts them in the left triangle. There are arguments that Bitcoin is actually centralized due to the fact that the mining industry is disproportionately in the hands of a few pools or corporations, which is why I think it's worthwhile to add...

A side note on bitcoin mining centralization

Mining centralization can either refer to

A small number of entities producing mining hardware or

A small number of entities controlling the network hash rate

The risks that arise from the first scenario include product defects, manufacturer price gauging, and ill-intended hardware manipulation that gives certain parties a higher chance of mining a block. In all these cases, the manufacturer would suffer more than the network because selling hardware at a much higher price and unintentional defects will harm the company's reputation and competitive advantage, and any manipulation is carefully audited for and is likely detectable by the network. [20]

While the network owes the majority of its hashing power to a few handfuls of entities, this is primarily an artifact of the arms race to obtain more advanced chips and physical infrastructures to operate/maintain the hardware. A long term view is that mining centralization will taper out as the economic incentives become less lucrative due to block reward halving, higher costs to obtain and maintain the most advanced chips, and limitations to how fast a more performant chip can be developed. [21]

Alternative mining protocols such as BetterHash are also being developed to decrease centralization by giving individual miners more control over block templates, allowing them to select the transactions they include in blocks rather than letting mining pool operators make that choice for them, all the while still benefiting from stable payouts. This also helps mitigate the risk of a government ordering a locally-operated mining pool to censor particular types of transactions. [22]

tackling the trilemma with second-layer chains

The canonical insight of Layer 2 solutions is that once we obtain the hard kernel of certainty provided by a public blockchain, we can use it as an anchor for cryptoeconomic systems that extend the complexity and usability of blockchain applications.[24]

2-way peg protocols (2WP) are protocols that allow cryptocurrencies to be "transferred" between the main chain (layer 1) to the secondary chain (layer 2). Under the hood, no cryptocurrency is transferred but instead temporarily locked on the main chain while the same amount of equivalent tokens are unlocked in the secondary chain. The original bitcoins can be unlocked when the equivalent amount of secondary-chain coins on the second blockchain are locked again in the secondary chain. [7]

Scalability solutions using secondary chains like Plasma, Loom, Alpha, Rootstock and Liquid derive from this general concept.

The security of a 2WP implementation depends on the incentives to enforce the 2WP promise by the critical parties taking part of the 2WP system. An overview of 2WP protocols:

Multi-sig federations

A federation is a group of notaries that serve as a middle layer between the main chain and a secondary chain. Their role is to (algorithmically) vote on when the user’s coins are locked/released. The clear downside to this is that they add another layer between the secondary and parent chain, and while this setup is still better than having a single controller of the funds, it centralizes control.

In multi-sig federations, the notaries control a multi-signature address for which the majority of them has to approve the unlock of funds. Ideally, notaries should have good reputation and security, and are geographically and juridically dispersed. There should also not be too few or too many. While the selected members of the federation have much to lose (reputation-wise) by misbehaving, the major drawback still stands that you have to trust them to act responsibly.

sidechains

Alternatively, what if each blockchain can enforces the 2WP lock/release premise through a consensus protocol? In other words, when

a proof-of-lock transaction is submitted into a block and

consensus is reached when that block is signed by a fixed number of parties and

the signed block together with the SPV proof is submitted to the main chain,

... the main chain automatically unlocks the equivalent amount its native coins and send them to the user. This requires the two chains to understand one another's consensus protocol.

Most public blockchains operating under proof-of-work consensus do not achieve absolute settlement finality, only probabilistic settlement finality. This means that immutability is based on an economic model as opposed to cryptographic hardness. In other words, we consider a block to be 'final' and immutable when the incentives towards manipulating transactions is offset by the costs to do so. As more proof-of-work gets submitted, older blocks become more expensive to manipulate. After the cross-chain ("exit") transaction has been submitted, there is a challenge period where the consensus group can present a lower proof-of-work and expect anyone to contest it. After a number of block confirmations, if the submission goes uncontested, the exit transaction will be accepted on the main chain. See Karl Floersch's great primer on the Plasma MVP for a demonstration of this.

drivechains

A drivechain gives custody of the locked coins to the miners, allowing them to (algorithmically) vote on when to unlock coins and where to send them. The miners vote using the main blockchain, and votes are cast in some part of the block. The greater the participation of honest miners in the drivechain, the more secure it is. Implementing drivechains on Bitcoin will require a soft fork for miners to validate new rules. [4] [7]Projects: Hivemind, BTC Codex.

Rootstock (RSK)

Rootstock is an smart contract platform that runs on top of Bitcoin. It features a 2-way peg drivechain connecting a Turing-complete layer 2 blockchain (RSK) to the Bitcoin blockchain. Smart contracts can be written and deployed on the RSK chain, enjoying its flexibility and speed while being secured by the Bitcoin network.

The RSK 2-Way Peg is designed to be a hybrid between all three of the 2WP protocols discussed above. When moving to the RSK blockchain, it uses SPV proofs of locked BTC in order to unlock sBTC on the RSK blockchain. To move back to the main chain in the intermediate development stages of the network, the RSK-BTC peg utilize a multi-sig federation/drivechain hybrid where the multi signatures are held by a combination the federation and POW of the miners. The federation comprises of major exchanges around the world, each one holding a private key for a multi-sig for a two way peg. A security protocol ensures that the same Bitcoins cannot be unlocked on both blockchains at the same time. [6]

Over time, the Rootstock team plans to have have the peg gradually switch to drivechain model and rely less and less on the federation, incrementally moving control to the miners, as described here and in the official FAQs.

The RSK Network involves

The RSK blockchain as a L2 technology running on top of the Bitcoin blockchain

Rootstock Virtual Machine (RVM) to execute smart contract code

A currency (sBTC) that is pegged to and backed by Bitcoin, used as gas paid to miners to run smart contracts and secure the network

A consensus mechanism (proof-of-work with SHA256 hashing algorithm like that of Bitcoin)

Miners, nodes, and a federation of well-known exchanges

And of course developers and end users [3]

To interact with smart contracts, you can send bitcoins to a lock-in account and receive the same amount of sBTC on the RSK blockchain. The transaction fee (gas) used to run the program is paid in sBTC to miners. When they want to cash it out, they send the exit transaction and the bitcoins that were lock-in gets released to them on the main chain.

Compatibility with existing infrastructures

Rootstock has designed the RVM to be compatible with Solidity and web3, which makes the blockchain compatible with smart contracts written for the Ethereum blockchain and its execution environment. By joining the flexibility of the EVM and the security of the Bitcoin network, the existing community of developers can choose to secure their decentralized applications using the Bitcoin network. In the future, RSK will be Java-compatible as well, opening doors the doors of smart contract development to those who are already experts in an already mature, widely used language. [2]

flexibility for developers and businesses

Backwards-compatibility with Ethereum gives developers an additional platform, consensus mechanism, and environments to choose from without having to duplicate the work. Building an DApp on this would be like building a hybrid car that can run on fuel in addition to another resource. When gas fees become too high, or if proof of stake isn't for you, now there is the option to utilize the Bitcoin network to run your smart contracts instead.

While running smart contracts on Ethereum uses gas, doing so on RSK uses SBTC, which is pegged to Bitcoin. To obtain 1 SBTC*, you can "lock up" 1 BTC on the parent chain to "unlock" 1 SBTC on the RSK chain. SBTC is therefore not a new native token and is backed by bitcoin itself. This also means that you can raise ICOs that accept bitcoin directly, keeping the funds in a cryptocurrency that functions best as a store of value and then issue your cryptoassets to your investors using smart contracts on RSK. [2]

*The satoshi denomination equivalent on RSK is a Rootoshi

Merge-mining

Merge-mining is a method that allows a secondary chain to utilize the hashing power of a parent chain to secure its network, allowing both chains to be mined simultaneously. An overview of how this works:

In the attempt to solve for the proof-of-work, miners "guess" nonces such that, when hashed with a block, an output is generated with certain number of leading zeros. The more leading zeros the network requires, the higher the block difficulty is regarded to be. In guessing for nonces and generating a hash, miners are constantly creating potential PoW solutions which are discarded if they don't produce the required number of leading 0s (i.e. meet the block difficulty of Bitcoin).

RSK takes advantage of these PoW solutions with lower difficulty to secure intermediate blocks, paying miners rewards to secure the RSK blockchain. The possible scenarios are:

A miner's PoW solution meets the Bitcoin block difficulty (and inherently RSK's)

The miner obtains both Bitcoin and RSK block rewards+txn fees

A miner's PoW solution meets the RSK difficulty but not Bitcoin's

The miner obtains RSK block rewards+txn fees

A miner's PoW solution meets neither chain's difficulty

Nothing happens - they have to try a new nonce and rehash

RSK merged mining therefore leverages the cryptographic work that is discarded in Bitcoin mining by using it to secure the RSK platform. What this means is that bitcoin miners can mine both Bitcoin and RSK at the same time and obtain block rewards for securing both chains while using the same hardware and consuming the same amount of electricity.

By giving miners the option to merge-mine for added profitability with negligible additional costs, RSK has thus far garnered support from bitcoin miners worldwide. [1][8]

Transaction fee distribution

80% of RSK transaction fees (gas costs to run smart contracts) will go to the miners who are doing the work to secure the blockchain. The remaining 20% will go to RSK. Out of this 20%, some will be allotted towards for further development of the protocol, and a portion will go to RSK full nodes as rewards for their contribution keeping the network decentralized. Eventually, the team plans to allocate some of the rewards to Bitcoin full nodes as well, which would make it the first time that a L2 solution directly contributes to decentralization of the first layer. The remaining portion goes to the federation that secures the Bitcoin-RSK 2WP. [2]

how do we prove that someone is a full node (stores the full blockchain)?

A proposed solution (under development) operates on "proof-of-Unique-Blockchain Storage" (PoUBS). This involves mandating the full nodes to periodically send broadcast hash digests of pseudo-random chunks of blockchain data in order to prove that they hold their own copy of the blockchain. They would need to be storing their own copy (instead of just asking a peer) to be able to broadcast these responses in time. [25]

The remaining full nodes that participate in the reward scheme can check other node’s responses.

further scalability with state channels

So far we have seen how RSK's layer 2 blockchain could add to scalability. In the first layer (Bitcoin), we take advantage of its decentralized, secure properties by regarding the native layer 1 coin BTC as a good long term store of value and sound money. The main chain as-is, without additional layers, would be less suitable if we wanted flexibility and fast transactions. Bitcoin processes ~4-7 transactions/second.

For flexibility, programmability, and speed we can look to the second layer blockchains like RSK which anchors to the first layer for decentralization and security, and run smart contracts by paying fees in second-layer coins to miners who are doing the work to secure the chain(s). These layer 2 blockchains can then serve as the logic layer for decentralized applications such as retail payments, escrow services, cryptoassets creation, supply chain traceability, online reputation/identity and prediction markets. Ethereum processes ~15-20 txn/sec. RSK processes ~100-300 txn/sec.

For comparison, PayPal processes ~250-400 txn/sec and Visa processes ~24000 txn/sec.

So right now RSK's transaction throughput is claimed to be comparable to that of PayPal. What can be done to improve on this?

State channels

A state channel is a two-way transaction channel between two parties (e.g. between two users or between a user and a machine). The transactions take place entirely off the blockchain and exclusively between the participants, which means that in-channel transactions are not subject to fees and transaction fees are only charged to "open" and "close" the channel, settling final state changes on-chain. State channels are the more generalized form of payment channels. Implementations of state channels can vary - notable projects include Lightning Network, Raiden, Trinity, and SpankChain. [17][18]

State channels make it more feasible to do micropayments or to 'stream' money. Transaction fees are only paid for state changes on-chain, which means that the channels enable us to do transactions like we would on the blockchain, but much faster and cheaper.

State channel implementations come with its complexities, which are described here.

Lumino is RSK's network of off-chain payment channels, which is claimed to allow up to ~20k txn/sec on sBTC or any token launched on the RSK blockchain. Some quick comparisons to other state channels: [26]

Lumino is more comparable to Raiden than Lightning, as the latter is built on a UTXO-based blockchain (Bitcoin). Lumino and Raiden are built on account-based blockchains (RSK and Ethereum respectively).

While Raiden created their own token which you need in order to utilize the payment channels on its network, Lumino uses sBTC which is pegged to bitcoin.

Lumino is also looking into one-to-many and many-to-one payment channels. Users can open many channels through a hub to connect to more than one peer, reducing the cost of locking and altering state.

I chose Rootstock as a case study for this article primarily because its infrastructural design involves an interesting combination of scalability solutions currently being explored in the space. In this article we got to look at different 2WP protocol implementations, state channels, merge mining, as well as proof-of-unique-blockchain-storage, which all emerge as part of RSK's implementation. This project was explored here for education purposes only and I am not affiliated with Rootstock in any way. Along with another smart contract platforms in the space, I'll be curious to see how RSK rolls out in the months to come.

closing remarks

This Halloween (31st October 2018) marks the 10-year anniversary of Bitcoin's whitepaper release by Satoshi Nakamoto. Over the past decade cypherpunks, cryptographers, engineers and software developers have been building out the internet of value that is enabled by blockchain and the protocols that drive it. Since my foray into the space in the middle of 2017, I've constantly been enamored by the rapid development and evolution of the space and community, which has been the primary driver of the content I create here. While my views have evolved since my first article on bitcoin, the idea of sound money, freedom, and financial sovereignty still lie at the core of my fascination for the technology that lies behind it.

As curious as I am about smart contracts running on Turing-complete blockchains, I'm still wary about the extent of its success as a "decentralized" alternative of current applications especially in relation to the promises that many ICO projects are making today. What's exciting about the altcoin market that it is a giant laboratory of experiment with decentralized networks. When it comes to secondary layers and sidechains, the big question that arises is the incentive structures and security around pegging assets to the main chain. Only time will tell what will solve the scaling problem for us, perhaps the answer hasn't even been thought of yet.

Of course, competition and capital influx has given us fertile grounds to be innovative, and perhaps a (small) number of existing projects will produce the long term, for-the-masses solution that will make all this debate worthwhile. I look forward to continue learning, contributing to the space and seeing how these platforms and protocols perform in the long run. For now I am happy with the outlook of a future with trustless digital bearer instruments enabled by decentralized infrastructures like Bitcoin - financial sovereignty secured by code.

Thanks for reading and I hope you learned a few things! Please leave a comment, share, or point out any mistakes you see. Until next time, 🥃

If you appreciated the post,

BTC: 3JaB3nHHfvWZVsnfHSNRepc8xAKubLSkZR 🙏🏼

Further reading & Resources

[Gabriel Kurman] Introducing Rootstock (RSK) [Video]

[IBM] Gabriel Kurman Interview [Video]

[Epicenter] Interview with Sergio Lerner - RSK Chief Scientist [Video]

[RSK] Drivechains, Sidechains, and Hybrid 2-way peg Designs [Overview] [Technical]

[Sergio Lerner] RSK Merge Mining and Bitcoin Interoperability

[Bitcoinist] Breaking Down the Scalability Trilemma

[Multicoin Capital] Models for Scaling Trustless Computation

[Preethi Kasireddy] Fundamental Problems with Public Blockchains

[CoinDesk] Layer 2 Technologies

[MIT Media Lab] The Importance of Layer 2

Transaction Speeds of Different Blockchains/layer 2 technologies

[Vaibhav Saini] Difference Between Sidechains and State Channels

[Vaibhav Saini] 10 State Channel projects you should know about

[Vaibhav Saini] 11 sidechain projects you should know about

[CCN] Decentralization of Mining with BetterHash [BetterHash BIP]

[Jimmy Song] How Mining Pools Work - Interview with BetterHash's Matt Corallo